Following the Path of the Cat in the Hat

Featuring a show & tell with the go-to expert on all things Dr. Seuss. Exploring evidence that the Cat was Black. Plus a Black writer's childhood memory of hiding Green Eggs And Ham from his mom.

For this week’s breaking news about Dr. Seuss, I decided to follow the path of the Cat in the Hat. This is the story of where it unexpectedly led.

Some years ago my wife and I stumbled upon a gallery that specialized in the art of Dr. Seuss.

Our children were young.

We wanted to inspire them to be readers — to pave their path to learning with curiosity.

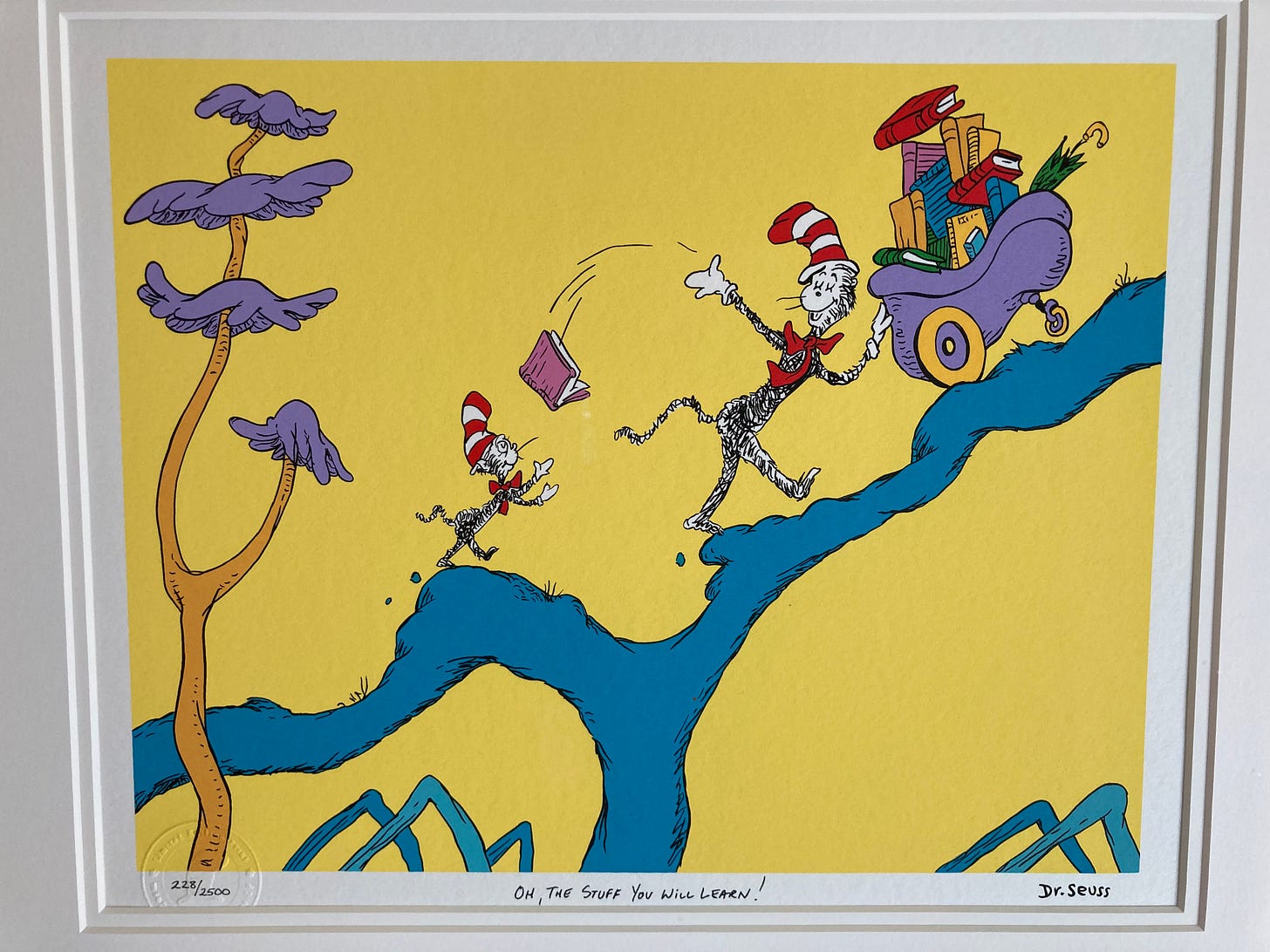

We bought the illustration you see below — and hung it near their bedrooms.

The image is from page 24 of I Can Read With My Eyes Shut.

Young cat! If you keep

your eyes open enough,

oh, the stuff you will learn!

The most wonderful stuff!

With those words and that image as my anchor, I explored this week’s news that the estate of the late Theodor Seuss Geisel — Dr. Seuss — would stop selling six of the author’s more than 60 books because they included racial and ethnic stereotypes that, in the words of Dr. Seuss Enterprises, “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

I contacted the go-to guy for the world of Dr. Seuss — children’s literature scholar Philip Nel, of Kansas State University. Professor Nel is the author of Dr. Seuss: American Icon.

I pulled out one of the offenders, which I found in my house.

Professor Nel says If I Ran The Zoo contains “two of the most egregious [images] in all of the six books.”

One is an offensive depiction of Asians in what Seuss calls “the mountains of Zomba-ma-Tant, with helpers who all wear their eyes in a slant.” The second:

The African Island of Yerka image in that book … is a racist caricature of two black men. In addition to the usual sorts of racist caricature … they also have been drawn in a way to accentuate their resemblance to the bird that they're carrying, which further ties them to animals.

On the other hand:

I think … one of the things that confuses people about the removal of these six books is that Seuss also did work like “Horton Hears a Who!” and “The Sneetches.” When published in 1954, one reviewer described “Horton Hears a Who!” as a rhyme lesson in protection of minorities and their rights. “The Sneetches,” from 1961, was inspired by Seuss’ opposition to anti-Semitism.

And then there is the case of On Beyond Zebra, one of the books on the list of six.

I remember “On Beyond Zebra” as this really kind of brilliant book that invites children to question language itself. It reminds us that language is an arbitrary system. The main character invents an entirely new alphabet to “…describe the things that he could not see unless he went on beyond Z,” which is wonderful, right? … So I thought “What could possibly be wrong with this book?

This week, after hearing the news, our Dr. Seuss scholar revisited that book, and found the offending image that had escaped his attention, which we discuss in our full conversation.

“It's been an evolution,” Professor Nel tells me, “and I have not always been aware of the degree to which Seuss’ imagination was steeped in the racist culture that he in some ways tried to oppose.”

As I continued my research, I discovered the BBC’s piece entitled The Surprisingly Radical Politics of Dr. Seuss, where I learned about a book called Dr. Seuss Goes To War. It features nearly 200 political cartoons that he drew before he became a children’s author.

In the book’s introduction, Art Spiegleman, the writer and illustrator of Maus, the Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel about a Holocaust survivor, writes that Dr. Seuss’ political cartoons in the 1940s:

“… rail against isolationism, racism, and anti-Semitism with a conviction and fervor lacking in most other American editorial pages of the period … virtually the only editorial cartoons outside the communist and Black press that decried the military’s Jim Crow policies and Charles Lindbergh’s anti-Semitism.”

And yet, a study of Dr. Seuss’ work conducted by Ramon Stephens and Katie Ishizuka of The Conscious Kid — a program that promotes healthy racial identity development in children — identified 2,240 human characters in Dr. Seuss’s body of work. Only 45 were characters of color.

Only two of the forty-five characters are identified in the text as “African” and both align with the theme of anti-Blackness. White supremacy is seen through the centering of Whiteness and White characters, who comprise 98% (2,195 characters) of all characters. Notably, every character of color is male. Males of color are only presented in subservient, exotified, or dehumanized roles….Most startling is the complete invisibility and absence of women and girls of color across Seuss' entire children’s book collection.

Which makes this week’s piece by Charles Blow, the New York Times columnist, particularly salient. He did not analyze the works of Dr. Seuss. He provided cultural context from his experience growing up Black in America.

As a child, I was led to believe that Blackness was inferior. And I was not alone. The Black society into which I was born was riddled with these beliefs. It wasn’t something that most if any would articulate in that way, let alone knowingly propagate. Rather, it was in the air, in the culture. We had been trained in it, bathed in it, acculturated to hate ourselves. It happened for children in the most inconspicuous of ways: It was relayed through toys and dolls, cartoons and children’s shows, fairy tales and children’s books.

After I read Charles Blow’s piece, I landed on a priceless Twitter thread by Michael Harriot, a senior writer at The Root, which he wrote after his sister texted him: “remember when you got in trouble for Dr. Seuss?”

Harriot begins the thread with “… the second most devastating day of my life: The day I found out The Hardy Boys were white.”

He then weaves the story of how his mother home-schooled him and his sisters — constructing a world around her children designed to insulate them from a culture in which Black people were defined by white people.

Here’s where Dr. Seuss enters the picture.

Harriot’s mother discovered the hidden contraband, which triggered “House Court,” used when he or his sisters got in trouble.

What I find so striking is the level of strategic planning, dedication and tenacity that Michael Harriot’s mom deemed necessary to raise her children with strong self-esteem, at a time when the Black characters featured in popular culture would not make a Black child feel proud —and the characters that would have inspired pride rarely, if ever, appeared.

And that is just some of what I’ve learned this week — by following the path — of the Cat with the books — and the words of advice — to keep my eyes open.

The Wavemaker Conversation

Now, I hope you’ll join me for my conversation with Philip Nel, which includes actionable intelligence for parents and teachers.

And if you find these Wavemaker Conversation newsletters entertaining, informative and/or perspective-changing, please take a few seconds to subscribe.

Among the highlights:

The Art of Dr. Seuss: The Uplifting, The Hurtful, and The In-Between

Revisiting On Beyond Zebra — On The Spot (9:53)

Scholars of Color: The Risks They Face (14:00)

Is The Cat In The Hat Black? (25:30)

Book Recommendations From Phil Nel’s Shelves (37:40)

To listen via podcast and read along with the transcript, click here.

For a deeper dive into the readings that informed this piece:

Michael Harriot’s Dr. Seuss Twitter Thread