Letters from Pleiku: A Memorial Day Pause

Featuring Iraq War Veteran, Novelist, and Poet, Kevin Powers. Plus, a conversation with the author of "In That Time: Michael O'Donnell and the Tragic Era of Vietnam."

“If you are able

Save for them a place

Inside of you…”

So begins the poem you are about to hear — Letters from Pleiku — written by an American helicopter pilot in Vietnam named Michael O’Donnell.

O’Donnell wrote the poem on New Year’s Day, 1970, three months before he was shot down on a daring rescue mission in the Cambodian jungle.

If you only have one minute — to pause — on this Memorial Day weekend — I recommend listening to Letters From Pleiku.

It is recited below by Kevin Powers for the Nantucket Book Festival’s online series At Home With Authors.

Powers served in Iraq in 2004 and 2005. He is the author of the Iraq War novel, The Yellow Birds, and a book of poetry entitled Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting.

It was during those lulls that Michael O’Donnell composed his poetry. Please click play to listen.

Introducing Michael O’Donnell

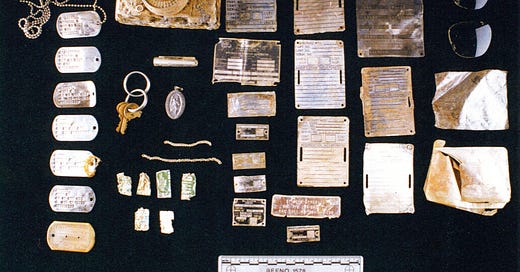

Letters from Pleiku was found, among other poems, with the personal effects of Michael O’Donnell.

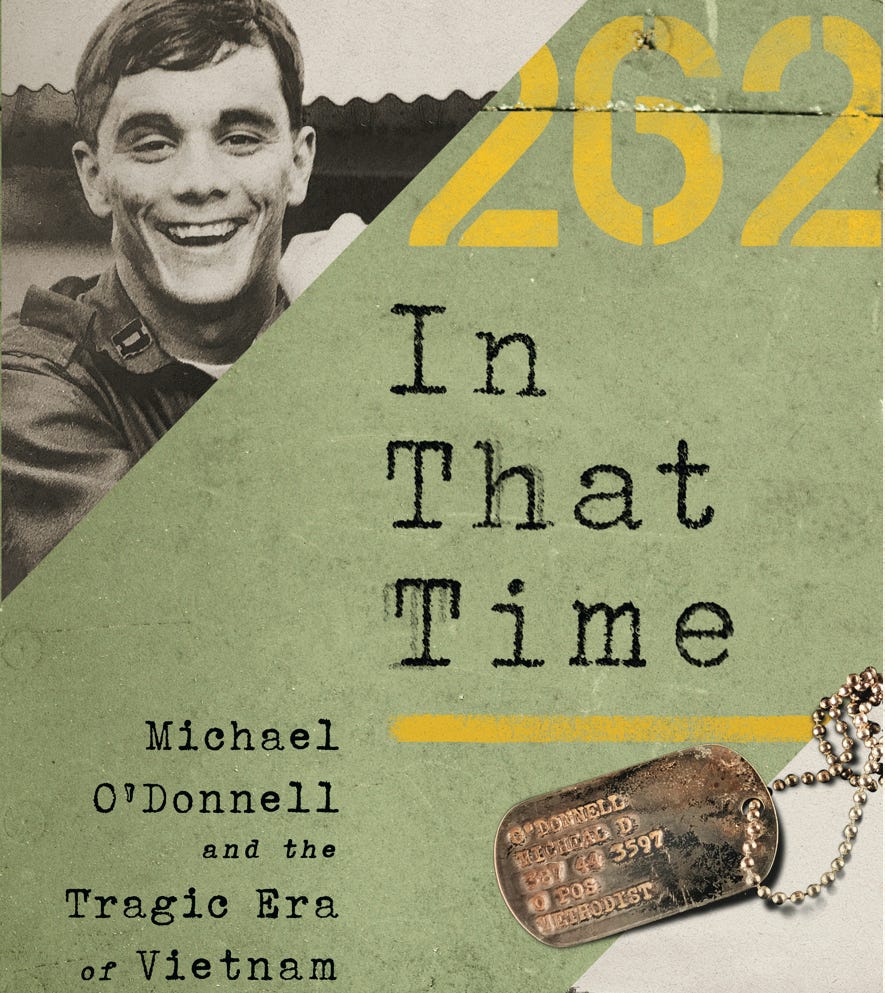

His story has now been documented by Daniel Weiss, CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in his book, In That Time: Michael O’Donnell and the Tragic Era of Vietnam.

Weiss, an art historian, is steeped in the classics. He writes:

Unlike the Greek warrior Achilles, who eagerly sought eternal glory through sacrifice in battle, Michael O’Donnell was in that poem asking for something more modest and poignant: that we simply remember the people who sacrificed everything for a cause that meant so little.

I spoke with Weiss about the rescue mission of March 26, 1970.

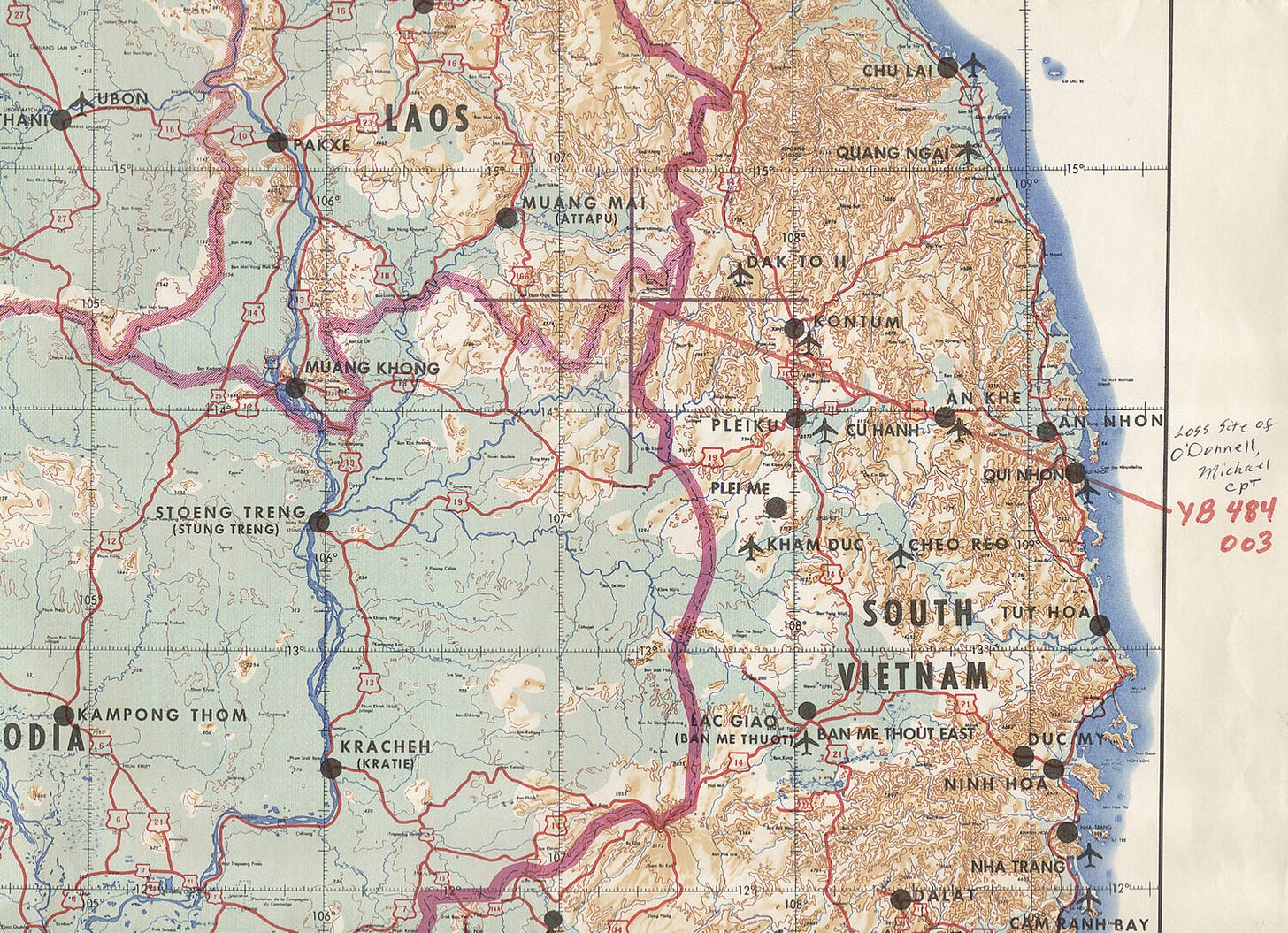

On this day, [O’Donnell] was called to join a team to rescue a group of commandoes who were under duress being chased by the North Vietnamese in the mountainous region of Cambodia just adjacent to the border of Vietnam. And they were told this would be a very dangerous rescue, that these guys on the ground had very little time left.

Weiss describes the complicated choreography of conducting such a rescue attempt.

… it involves about seven or eight helicopters, two or three fixed-wing aircraft, all operating in a choreographed way to protect each other and to save the soldiers on the ground. They all flew into formation … a thousand feet, fifteen hundred feet above the action in Cambodia, waiting for these commandoes who were absolutely running through the jungle being traced by the enemy, and the situation was deteriorating very rapidly.

And then, time ran out.

Most of the rescue aircraft had to make a 40 minute round trip to refuel — leaving O’Donnell and his crew and two other support gunships hovering. As the eight commandoes on the ground radioed that they were about to be overrun — O’Donnell moved in.

… He went down by himself through the jungle canopy, very carefully maneuvering his helicopter in very treacherous space, surrounded by the enemy. And he set down the helicopter on an area of ground. And then he waited four minutes on the ground for these commandoes to get there. Under enemy fire for four minutes, in that situation, is as exposed as you can be. But he waited. And the commandoes arrived, they got on the helicopter and he began to climb up out of the canopy once again.

By this time, the other U.S. aircraft had returned.

And as O’Donnell cleared the trees, he said “I’ve got them all, I’m coming out,” and he started to accelerate forward and climb. And at that moment, the helicopter was hit by a missile from the hillside below. And he was moving forward fairly quickly, so the helicopter continued moving forward for another hundred or two hundred yards before it then plummeted into the jungle canopy, and there was a burst of flames and smoke.

O’Donnell was listed as missing in action. It would be three decades before the wreckage of his helicopter was found, and the remains identified.

Peter Osnos, who published In That Time under his PublicAffairs banner, was a Washington Post reporter based in Saigon during the war.

It was the first “living room” war. It was the first war where you could watch the battles as they took place because there were cameras there and it wasn’t a newsreel. It was not quite real-time, but almost. So you had this extraordinary sense of a war that was being fought far far away, by a great many young people, that no one really understood or could define. I think the defining characteristic of our experience in Vietnam was ignorance. We didn’t know the country, we didn’t know the people, we didn’t know their history …. And that’s why all of these fellows who gave their lives, we all can understand why, when you look back on it, you say “what the hell was that about?”

58,220 American citizens died in the Vietnam War. Vietnamese losses — soldiers and civilians — were many times more than that. Weiss reminds us of those numbers, before turning to what he calls the story he has carried with him for many years.

… I wanted to kind of unburden us of the statistics of the war and just get to know this one person. And if we can feel something about him and his life and his loss and the loss of those who loved him, then … we come just a little bit closer to understanding the nature of sacrifice in circumstances like this …. I really wanted to try to tell Michael’s story in that way to connect the readers to what it means to lose someone in war.

On this Memorial Day, thinking of those who have served, and sacrificed — and those who have had to live with the loss — “save for them a place inside of you.”

To learn more about Michael O’Donnell and his place in the history of the war in Vietnam, please listen to my conversation with Daniel Weiss and Peter Osnos for The Nantucket Book Festival’s At Home With Authors series.

To receive the Wavemaker Conversations Newsletter in your inbox, please take a moment to enter your email and subscribe.

And for meaningful additions to your home library …